New Relationships and Arrivals

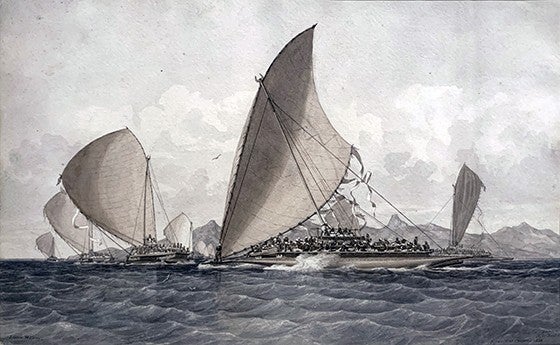

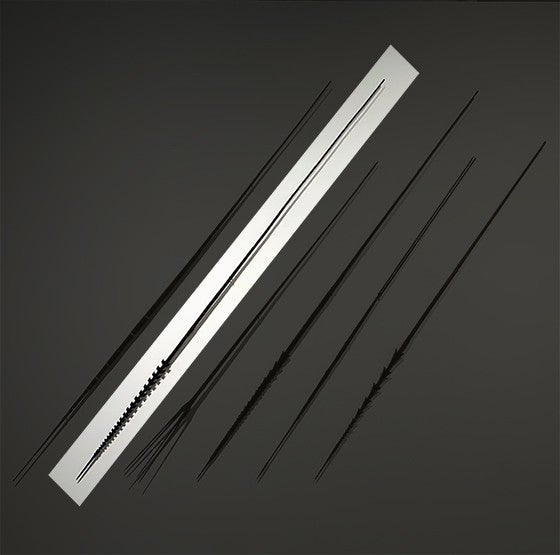

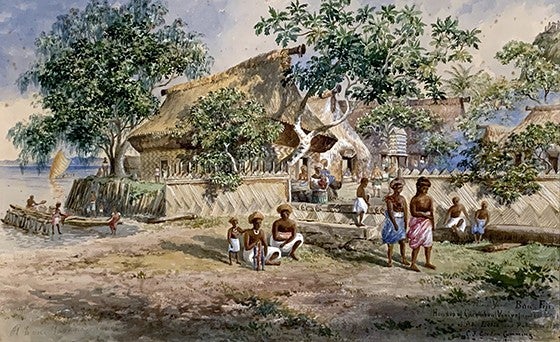

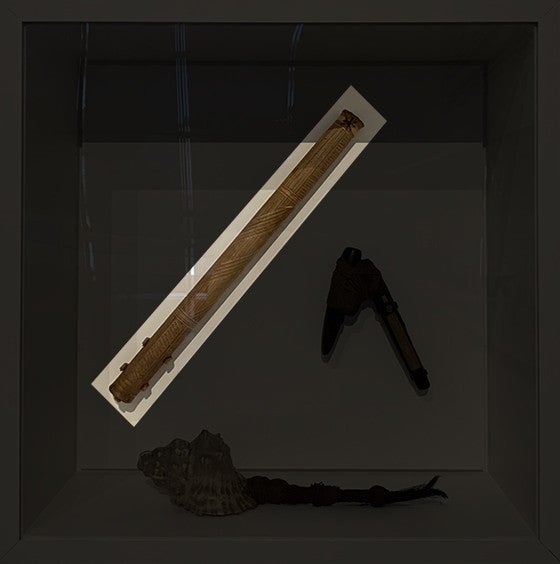

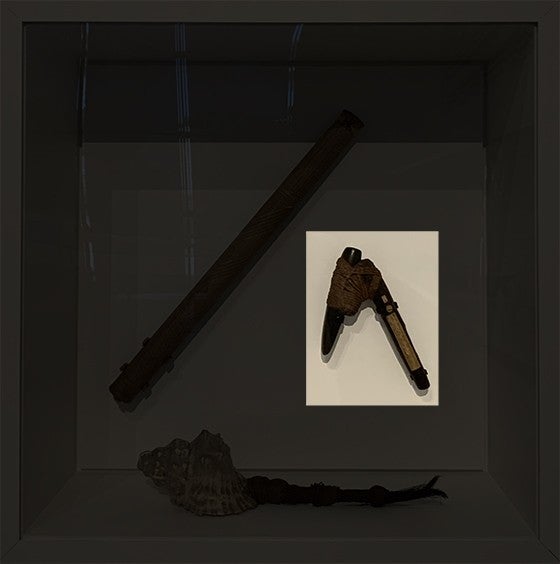

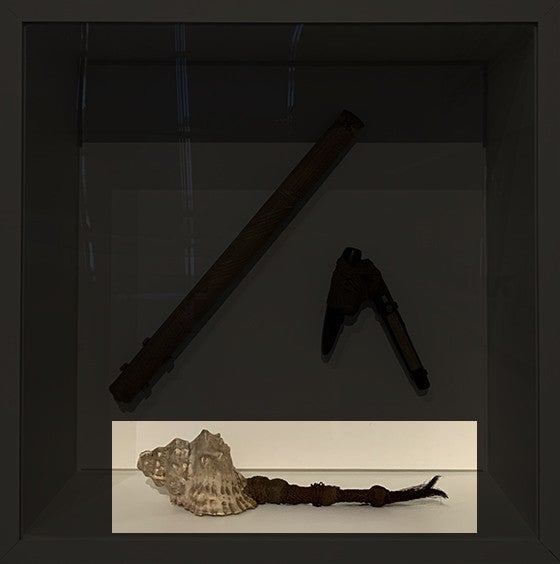

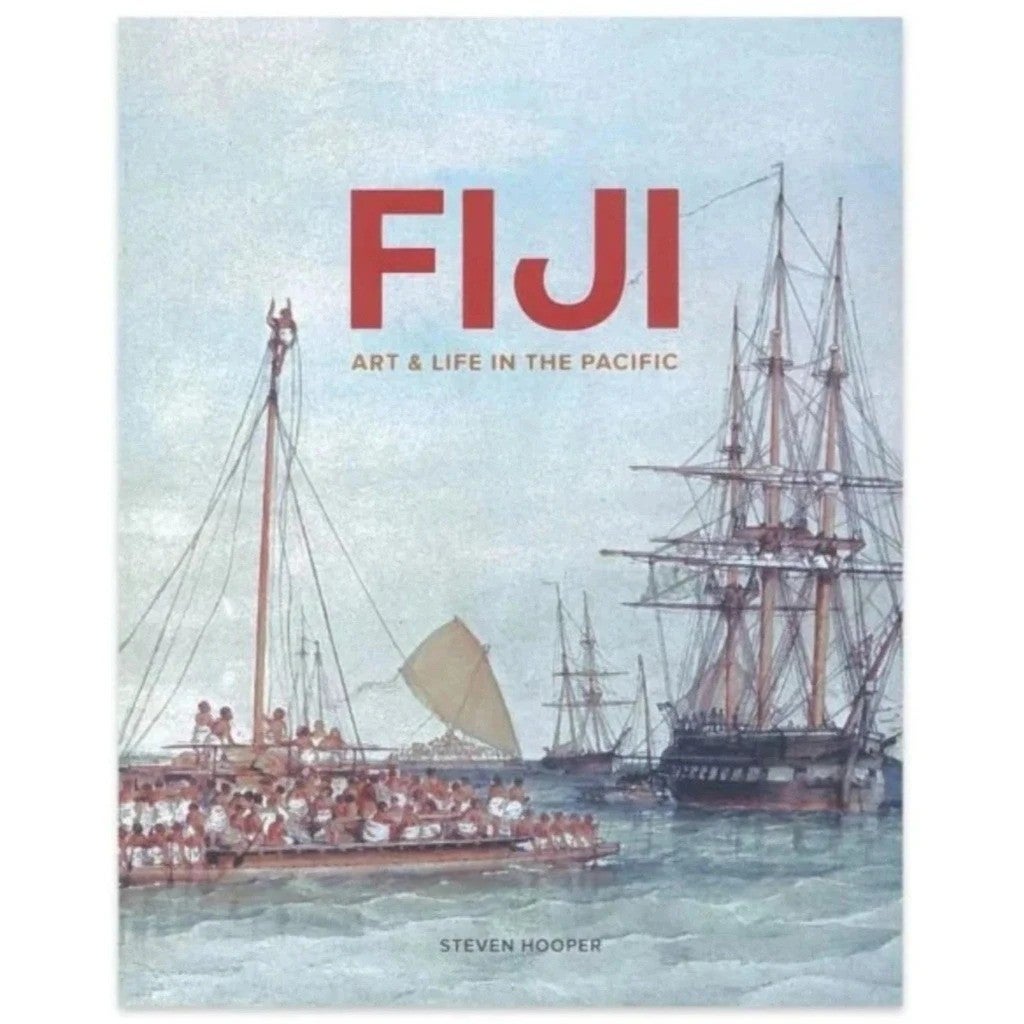

In the nineteenth century, Fiji established relationships with new visitors and settlers through trade and exchange. Initially, traders seeking sandalwood and then sea cucumbers (bêche-de-mer) for trade with China called in at places such as Bua Bay on Vanua Levu. Following those travelers, Russian, French, American, and British naval expeditions made scientific and diplomatic visits. Leading Fijian chiefs, in a ploy to create an alliance with the most powerful chief at that time, offered in 1858 and later in 1873 to cede Fiji to Queen Victoria. The Deed of Cession was signed in 1874, and Fiji became a British Crown colony until independence almost a century later, in 1970.

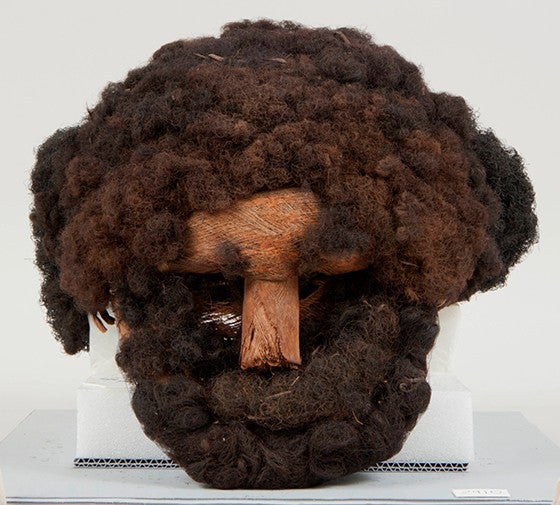

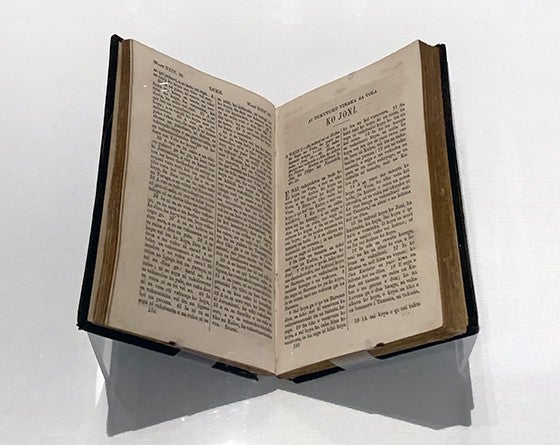

Meanwhile Christian missionaries, initially Methodists and later Catholics, established missions at chiefly centers in Fiji, the first in 1835 at Tubou on Lakeba in the eastern Lau islands. By the late 1870s, most Fijians had converted to Christianity, but still retained respect for their ancestors, who were embodied in their elders and chiefs. Relationships with outsiders were often managed and maintained via reciprocal gift-giving and exchange. European visitors and residents became keen collectors for scientific and souvenir purposes.

c. 1000 BCE

The Lapita people arrive first from the west; continuing population movements and migrations thereafter

c. AD 1000

Voyagers sail east from western Polynesia to settle the rest of Polynesia; continuing periodic arrivals from the west and regular interactions with Tonga and Samoa

1643

The Dutchman Abel Tasman visits Tonga

1774

James Cook visits Vatoa in southern Lau, Fiji

1804–14

Sandalwood trade flourishes in western Vanua Levu

1820s–50s

Bêche-de-mer trade in Koro Sea region of eastern Fiji

1835

Methodist missionaries arrive in Lakeba, eastern Fiji

1840

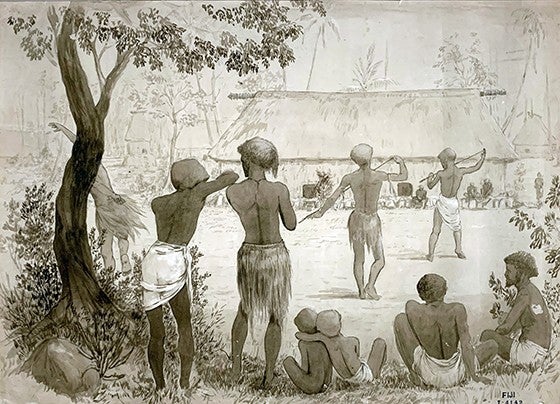

Three-month visit to Fiji by American Captain Charles Wilkes of “The United States Exploring Expedition”

1838–42

American Captain Charles Wilkes leads “The Exploring Expedition” to Fiji

1843–55

Bau-Rewa war; the Tongan Ma’afu arrives in Fiji and establishes a base in eastern Fiji

1854–57

HMS Herald conducts extended surveys in Fijian waters

1871–74

Ratu Seru Cakobau of Bau attempts to unify Fiji under a “Cakobau government”

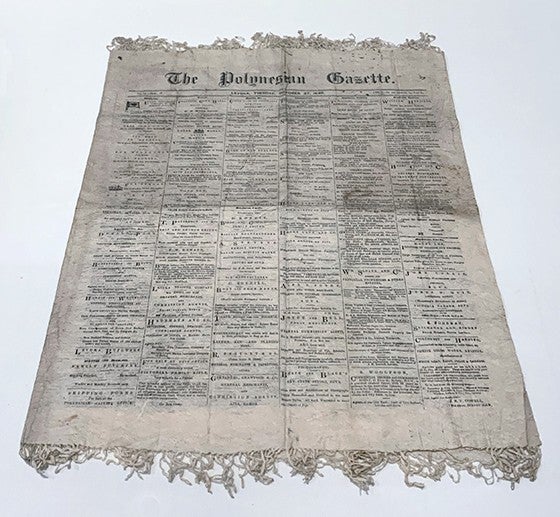

1874

Deed of Cession signed; Fiji becomes a British Crown Colony with Levuka as the capital

1875

Measles epidemic devastates one-third of the Fijian population Sir Arthur Gordon becomes first resident Colonial Governor

1879

First indentured laborers arrive from India to work cane fields

1883

Suva becomes the capital of Fiji; death of Ratu Seru Cakobau, Vunivalu of Bau

1904

First Legislative Council with both European and iTaukei (indigenous Fijian) representatives

1914–18

World War I; Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna enlists with French Foreign Legion and is awarded the Croix de Guerre

1939–45

World War II; Fiji Army heavily involved in the Solomon Islands campaign; Corporal Sefanaia Sukanaivalu posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross

1970

Fiji gains independence from Britain and joins the Commonwealth of Nations; Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara is Prime Minister

1978

Fiji begins active role in UN peacekeeping missions; continues to the present

1987

Fiji becomes a republic

2016

Fiji becomes the first country to ratify the Paris Agreement (UN climate change treaty) Peter Thomson, previously Fiji’s Permanent UN Representative, elected president of the United Nations General Assembly Fiji wins its first Olympic medal, a gold in Rugby Sevens, at the Rio Olympic Games

2017

Fiji co-chairs the United Nations Oceans Conference, New York Fiji assumes the presidency of the COP 23 (Conference of Parties), and chairs United Nations Climate Change Conference, Bonn

2018

Fiji joins the United Nations Human Rights Council